General Considerations

Some Orders of Magnitude

An economic zone like the Euro one has an average life span of eighty years in 2012, we obtain:

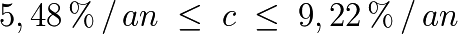

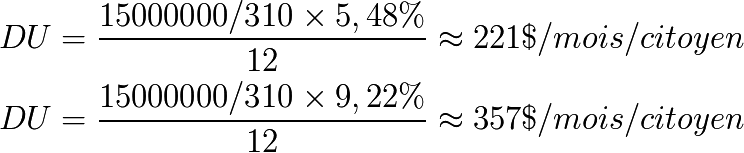

To already give an idea of orders of magnitude, we can make a comparison with real data from 2010. Take the example of the Euro Zone with 10,000 billions of Euros and 330 millions of citizens, the optimized Universal Dividend would be included between:

and

Which means between 552€ and 928€ per month for a family of four individuals.

Reality shows huge disparities within the zone regarding the existence of a minimum individual income since in France or in Germany we conditionally reach 450€ per month per individual (condition of age, of resource, etc.), compared to countries like Romania or Bulgaria, where there is a minimal salary of 130€ per month per individual, and without money allocated individually.

We are, in Europe, in a case of high spatial asymmetry which results in the creation of high disparities and a transfer of economic activities from countries with high individual monetary allocation (which are discouraged to produce goods and monetized services), to the countries with almost no individual monetary allocation. This essentially implies that equality between individuals is not recognized within a common economic zone.

If the ins and outs of monetary creation had been presented to the individuals of this community, and thus their own approval had been required to organize this common currency, they would have realized the encountered difficulties regarding ethics, fairness and symmetry of monetary creation, and they would surely not have accepted it in such conditions.

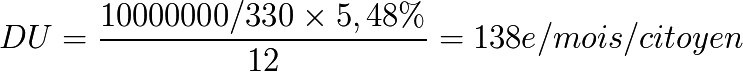

In the USA, the optimal universal dividend is calculated for about $ 15,000 billion in circulation and 310 millions of residents for a 80 years life span. It would be between:

With these remarks, we will see later that the installation of an Universal Dividend can be progressive and does not have to be fixed to a given monetary state to be organized. The given numbers here aim to explain the mechanism, and to give orders of magnitude at the moment the calculation is done. One must not forget that the money supply is not a fixed quantity, it evolves in space and time, and any measure must only be understood as a local and instantaneous snapshot.

NB: In addition, Yoland Bresson points out that the GDP is between two and three times the money supply at various stages, and we may consider that an unconditional basic income could be based on two to three times the Universal Dividend, that is in 2010 approximately 400€ per month per citizen in Europe, or $600 per month per citizen in the United States. We then make the difference between the Universal Dividend as an individual monetary creation and the Basic Income, which includes the Universal Dividend and a share of redistribution. We can also apply the temporal symmetry principle not only to the immaterial circulating currency but also to the property rights of the prime matter in a more global way, which leads to at least double the transmitted value in time if we consider that money reflects the existing value. But this consideration is beyond the frame of the RTM itself.

These remarks associated to a range of possible values for “c”, give a range of acceptable values in 2012 for a Basic Income (and not only a Universal Dividend) between 200€ and 800€ per month per Citizen for Europe and $300 to $1200 per month per Citizen in the United States. This data from 2010/2012 is obviously to be calculated again depending on population, life expectancy and money mass variations.

About Value

The argument that the money supply’s inflation would be unethical, because it would depreciate what individuals own doesn’t hold when confronted to both a global and a local analysis.

First of all, the consideration of life expectancy and fair monetary creation toward all generations discards the argument from a temporal point of view before our descendants who shouldn’t be excluded from the process for our benefit.

Then, even from a local point of view the argument is flawed before a subtle analysis.

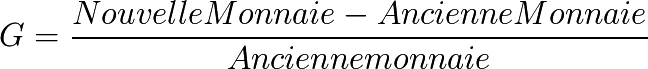

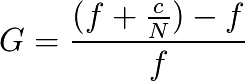

Let’s consider an individual or an individual collective “X” among the N of the economic zone who owns a fraction f of the entire money supply. X receives therefore a fraction of the dividend c / N which means that his ratio of personal monetary “gain” is:

So:

And thus:

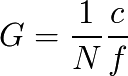

That means that his ratio of personal gain G will be greater than c if he owns less than M/N of money, it will be equal to c if he owns exactly M/N money, and less than c if he owns more than 1/N of money.

It therefore depends on the currently owned quantity of money that one can estimate to benefit or not in monetary terms.

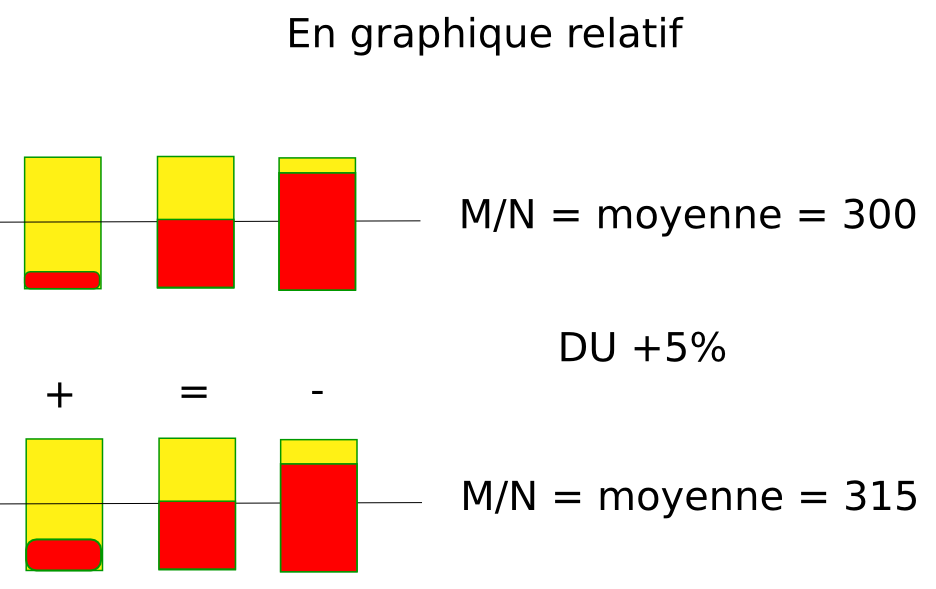

Numeric example: A owns 50, B owns 200, there are other individuals in this monetary community and the money supply is 1000, for a community of ten members. Let us assume a life expectancy such that the UD is 5% per year.

The Annual Universal Dividend allocated to anyone will be 5% × 1000 / 10 = 5. A will have then 55, and B 205. Locally, A has benefited of 5/50 = 10% of additional money, instead of 50 / 1000 = 5% and B owns 205 / 1050 = 19.52% of the money supply compared to 200 / 1000 = 20% before the distribution. B has seen his share of money reduced because he owned before the distribution more than 1000 / 10 = 100 of money, whereas for A, under the average, the opposite happens.

However, if X owns more than M/N of money, which is more than the average, the money supply that he doesn’t own will be, on average, per individual, mechanically less than M/N, so the prices adjusted downward due to local deflation.

Thus, although his quantity of relative money won’t grow as fast as the global mass, he can benefit from lower prices. In addition, if he owns less than M/N of money, the prices could have a tendency to increase for the opposite reason, and what was won relatively to the money will be lost relatively to the values.

Graphical example with three individuals, having a monetary distribution of 300, before Universal Dividend, then after. The evolution of their relative situation is different depending on the relative share of money owned by each of them.

In relative theory where analysis includes the relation between parts and the whole, Local + Non-Local = Global. This means that everything chosen individually has an opposite effect on the rest of the economy. If the money is hoarded, it is a force that tends to lower prices where the money becomes scarce, and if the money flows, it has an effect which tends to raise them (at constant levels of production, excluding innovation. Innovation prevents the comparison in time, cf. the principle of relativity).

Finally, value is obviously not money. The value for which X can aim for, includes the goods he owns, which includes admittedly the money, but also the goods he could buy with his money, as well as the money he could get by selling his goods.

Thus, the arbitration that X can make could depend only on his personal choices about the quantity of money he wants to include in his goods or not, the good he wants to hold, sell, or buy, and certainly not only the quantity of money he owns. Moreover, in an innovative economy where the members are encouraged to create new goods and services, what will be value tomorrow is to a large extent totally unpredictable.

But furthermore, before and after the distribution of a Universal Dividend, prices of the non-monetary goods can evolve too. There is, thus, no possible, simple and generalizable conclusions about the monetary distribution, if only that it is not favorable nor unfavorable for all, all the time, but its beneficial effect or not depends on the concerned individual and how the monetary surplus will be distributed on one hand, and used by the individuals on the other hand.

Also there is no certainty possible about what should be done in order to “protect” one’s capital, which is also here a purely relative value (“Le Douanier Rousseau” - TN: a French painter who died in poverty but whose paintings are now worth a fortune - would be surprised to know the estimation of his capital carried out in 2010, and Maxwell even more if he still owned “intellectual property rights” on his fabulous theory on electromagnetism).

Moreover the Universal Dividend is without absolutely no prejudice, in terms of personal gains or loss, regarding “value”. It is the individual choices which determine the impact of the money supply’s increase on the individual basket of values.

About the symmetry of the value brought by individuals

One should really understand the symmetry argument in its entirety. Members of an existing monetary system have benefited from the initial monetary creation, but are not necessarily “rich” of this particular money. They are most of all rich of the goods, the skills, the fundamental nature of the human being able to trade with his siblings and to have a unique opinion about what is value or not. Yet the value which exists inside this community of individuals has no reason to take priority over the value estimated by the future newcomers.

This is true both spatially and temporally. That is to say that when two communities decide to integrate with one another, and so to merge their money, one should not take precedence over the other in terms of monetary creation per individual, and when a generation replaces another, one should not suppose that values realized by the next generation would be less legit than the previous.

That is why it is a relative theory of money. There is no individual referential privileged regarding the measure of value, each individual constitutes an acceptable reference to get a measure, and only the money, contractually admitted by the members of the economic zone is a common measure of value.

It is the same as in relativistic physics, we have between two relative references only one common measurement standard which is the speed of light, from which observers agree, and transform their view of the phenomenon (time, space, etc.) in relation to the chosen reference. Yet this measure, although common, is not “absolute” as a result of the expansion of the Universe. The speed of light in relation to the volume of the Universe decreases over time.

It is the same for the money coming with a growing economy in space-time. The succession of human generations built upon each other, creates higher or different values in a process of quantitative and/or qualitative improvement (which can also manifest itself by a reduction of some streams due to the optimization of their use).

Even in the case of stagnation or regression (we can think of the case of the North American Amish who refused to integrate technical “progress” in their community), the community enriches itself in terms of knowledge, lived experience, which in the long term will constitute without any doubt a value related to the experimental knowledge acquired in this way whatever the interpretation. No doubt that the evaluation of economic value for the Amish differs significantly from one of another community.